It is common knowledge that not enough women pursue philosophy after graduate level. There have been numerous explanations offered, and advice suggested, but as yet no change. This article by no means gives a complete overview or answer, but is an attempt to throw the focus of the problem onto one area, that of perception. How people look at females consciously or unconsciously and how people regard the status and function of philosophy may be working in conjunction to prevent bright young female minds from progressing. I will argue that there is nothing innate in the brains or personalities of females to justify the trends. I don’t think it is good enough to claim that women are simply not interested in the technical rigour of the subject, as if they are somehow ‘above’ such irrelevant abstractions. I think this flatters to deceive, and prevents us addressing some more fundamental issues.

I will not be discussing the issue of sexual discrimination in academia. This is something that needs detailed and careful discussion and I am not qualified to do it justice. I hope someone does. Rather this is a very partial discussion of some of the theories for female underrepresentation in philosophy.

Facts and figures …

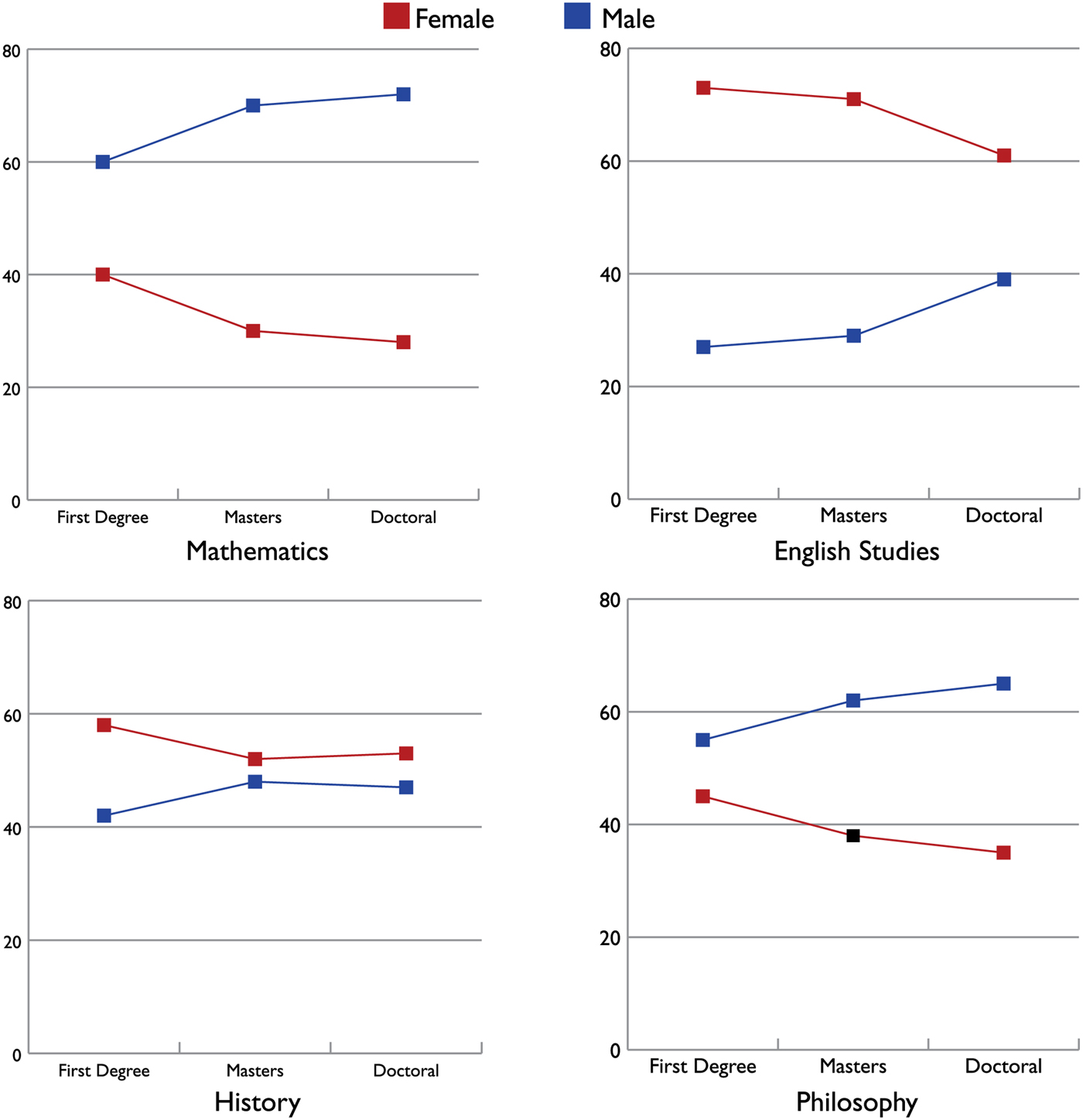

The picture is this: the British Philosophical Association and the Society for Women in Philosophy UK produced a report in 2011 using their own data and data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency which showed that of a sample size of 134 university Professors, 19 per cent were women. When philosophy was compared to mathematics, English and history regarding academic progression the following was shown:

Reproduced with permission from BPA/SWIP

There was a reduction in the proportion of women from undergraduate to PhD levels in all four subjects, but it was most marked in mathematics and philosophy. There is little gender bias in philosophy at undergraduate level, with 45 per cent of first degree students being female. At A-level, the only exam board offering Philosophy as a stand-alone qualification is AQA and they informed me that they do not keep statistics on candidates’ genders, so I will have to accept anecdotal evidence that the trend continues downwards in the academic ladder, with females often outnumbering and outperforming males at A-level. Something is happening higher up the academic ladder. Either women are naturally less suited to advanced philosophy or they are suffering some disadvantage, imposed or self-imposed, that stops them from developing genuine talents.

Brains?

When we see that mathematics and philosophy experience the same reduction in females at Masters and Doctorate level, there is a temptation among some to claim that male brains are more suited to the logical reasoning skills required for these subjects. The ‘left brain/right brain’ theory is often evoked whereby men are more left brain dominant and women more evenly balanced between the two hemispheres, making them better communicators and more intuitive. This would explain the higher numbers of women in English. But let us look at what is actually being claimed here, as reported in ‘Male and Female Brains Wired Differently’ (The Scientist Magazine, December 2013).

In a study run by UPenn Perelman School of Medicine radiologist Ragini Verma and colleagues scanned the brains of more than 400 males and more than 500 females from 8 to 22 years old and found distinct differences in the brains of male versus female subjects older than age 13. The cortices in female brains were more connected between right and left hemispheres, an arrangement that facilitates emotional processing and the ability to infer others’ intentions in social interactions. Verma states:

So, if there was a task that involved logical and intuitive thinking, the study says that women are predisposed, or have stronger connectivity as a population, so they should be better at it.

Surely that is exactly what makes a good philosopher? The ability to follow logical structures and form tight analytic arguments, but also forming intuitions about the conclusions and the applications? Helen Beebee in Women and Deviance in Philosophy (2014) uses the example of Gettier illustrations where we form the intuitive conclusion that something is not ‘knowledge’ (although this is in the context of an interesting discussion about intuitions in general and should be read in full). It sounds to me that if philosophy is being regarded in the proper way, as something complex and technical that also involves intuition and practical implications, then women’s brains are quite perfectly suited for it. I’m not sure that talking about ‘the female brain’ is actually helpful, but my point is that it cannot be used to explain the gender imbalance in philosophy.

Personality?

Given, then, that the female brain is in theory no less capable of advanced philosophy than the male one, is there something about the particular academic climate which is putting women off?

Helen Beebee suggests that philosophy by nature is adversarial, being a process of argument, counterargument, pointing out weak premises and invalid conclusions and this is a necessary process to progress the discipline. But although the content of academic philosophy is adversarial, the style in which it is conducted is unnecessarily confrontational. Phyllis Rooney (2010) points out the warlike metaphors (shooting down points, attacking positions, and so on). She argues that a combative seminar style can be alienating for women. Her point is that if there is an implicit bias (which I assume would be that women are an easier target, somehow weaker in the field of war) then this is enough to trigger a stereotype threat (a negative effect on women, perhaps in terms of increased stress and anxiety when in the seminar room).

At this point I want to refer to Mary Warnock, who talks candidly about female philosophers in the book What Philosophers Think (edited by Baggini and Stangroom, 2003). As one of Britain’s most famous female philosophers, one would perhaps expect her to by flying the feminist flag, but this is not so. At times she is rather scathing. Regarding the claim that women may find it harder to defend their views, she rejects this outright.

I’ve never known such adversarial people as women philosophers. I certainly don’t think that they’re timid little creatures that can’t speak up in a seminar. Far from it – they sometimes dominate the scene. Women are rather garrulous. I see no symptoms of a male set up.

I’m not sure that all of this is particularly helpful. Would one use the term ‘garrulous’ to refer to a male philosopher contributing at length to a debate? But Warnock does seem to be rejecting, at least anecdotally, the claim that women are ‘performing’ less well due to either perceived or real threats, or that they are intimidated by the adversarial nature of the subject. I think this adversarial nature could result in stereotype threat for certain people. Some people are far less comfortable forcefully defending their views and as such the milder character may be subject to an implicit bias. I’m not convinced that this is a gender issue, but it is certainly something we need to address in the discipline. As Beebee rightly points out, the inability to think of an off-the-cuff response to an issue is not an indication that one’s theory is not sound. A response is no less valid if it takes a few hours or days to formulate. Philosophy will lose out on great minds and ideas if it is hostile to the person who doesn’t want to engage in unnecessarily aggressive debate. But I am uneasy with this being something that only women face.

Looks?

So far I have expressed some scepticism about the female brain or personality being any sort of innate disadvantage to advanced philosophical studies. But I do think that the perception of women’s nature or character and the perception of some areas of philosophy may lead to the self-selection of women out of philosophy. I think that this happens before they reach the seminar room and is something much more fundamental in society which impacts on how women look at philosophy and how philosophy looks at women.

Looks, in the sense of image and perception, matter greatly, and there is a deeply permeating view of the female ‘nature’ that may mean we are not giving them the chances they need.

In her hugely influential anthropological paper ‘Is Female to Male as Nature Is to Culture’ (1974) Sherry Ortner outlines the universal subordination of women and their association with nature, the domestic and private sphere. The female psyche is often seen as more emotional and irrational. Males are associated with culture, rationality, the public sphere of life. She claims we are confronted with the tradition that women are seen as more practical, pragmatic and this-worldly than men. In other words, female concreteness vs male abstractness. She claims the feminine personality is perceived as being involved with concrete feelings, things and people rather than abstract entities, with the subjective rather than objective. Now the point of implicit bias is not that these characteristics have to be true. Indeed, Ornter agrees that these characteristics should not be taken to be innate. They just have to be perceived to be true. They are likely to be the result of the universal socialization process women experience, where their role is seen as nurturer within a private domestic sphere. Mary Warnock herself illustrates the pervasiveness of this view when she tries to explain the historical trend of female philosophers being primarily concerned with religion and ethics.

I think that most women, even the cleverest of them, were locked in the traditional role of being the supportive, probably religious members of the household who held everything together.

Could it be that the association of women with certain ‘softer’ areas of philosophy is coupled with the perception that these areas are of less philosophical worth than the more technical areas? My own experience, having completed my first-year undergraduate exams, was being advised to take modules such as mind and metaphysics over religion and ethics ‘to get more respect’ within the department.

David Papineau, in his review of the collection Women in Philosophy: What Needs To Change (edited by Hutchinson and Jenkins, 2014) in which Helen Beebee’s article appears, drew on an analogy with snooker, where there is also a lack of female participants at the highest levels. He quotes Steve Davis, who claimed that it is not the case that women lack the skill to compete at the top level, but rather they don’t want to. They are disinclined, as a group, to devote obsessive effort to ‘something that must be said is a complete waste of time – trying to put snooker balls into pockets with a pointed stick’. Practising eight hours a day to reach world-class level is one of the most ‘stupid things to do with your life’.

Papineau sees philosophy as being especially scholastic and technical (this would also apply to mathematics). The technical minutiae may not always have an obvious practical impact. Ortner’s claim to the universal perception of women as more subjective, practical and concrete would map onto this. It’s worth stating once again that women do not have to be innately like this to suffer stereotype threat. All that is needed is for people to look at women as not suited to such abstract philosophy for women themselves to accept that perhaps this is true. If this perception that women should not be doing something impractical and abstractly technical is as deep rooted and universal as Ornter suggests, then we are in trouble.

Papineau elaborates:

One doesn’t have to be an enthusiast for ‘impact’ to suspect that the main point of much of this technical work is to enable young scholars to display the kind of super-smartness that their elders so prize. Placing a premium on brilliance creates a pressure to work in a style that requires it.

(I assume that this ‘style’ is one of focused, often obsessive dedication.)

This may turn women away from brilliance-prizing disciplines, not because they can’t play the game, but because they won’t. Most young people come into philosophy … to address important issues, not to make the next move in technical exercise. When they discover that they need to dance on the head of a pin to get a job … many women will see it as the intellectual equivalent of putting balls in pockets with pointed sticks, and conclude that they could be doing something better with their lives.

This made me think about the many hours I spent before my final undergraduate exams studying the reason a right hand cannot fit into a left-hand glove unless there was a fourth dimension of space. Was there any point? (Yes, absolutely, but I’m coming to that.)

Papineau suggests that if the technical nature of the subject was the reason for the scarcity of women, then it raises fundamental questions about the nature of the subject, and we should consider which topics really need philosophical attention.

My interpretation of Papineau is this: he is adopting the universal perception of women that Ortner has outlined. If it’s too abstract, without relating to real things and people, then women don’t want to know. They don’t really want to play these pointless, perhaps egotistical games. Secondly, it appears that he is suggesting we rethink the curriculum. Perhaps we should remove some of the more technical and abstract areas. If I am correct in this interpretation then I think this would be a mistake.

Philosophy isn’t snooker …

Do women opt out of advanced academic philosophy because they don’t see the point in it? This would assume a universal ‘nature’ of women, as we have discussed above, and there are dangers in this. But if this is a prevailing perception, then perhaps the implicit bias that women will not, should not or cannot do this sort of thinking creates enough stereotype threat that they self-select out. I reiterate that I think the stereotype threat from this perception of women is more fundamental than anything to do with combat in the field of debate and that it is better at explaining trends as it is more clearly specific to the perception of women as a group. Perhaps we regard the young girl who wants to spend hours on a logical puzzle with less indulgence than the young man. Perhaps we put the question ‘what will you do with that?’ more often to young women than men wanting to study postgraduate philosophy. I don’t know, but I do suspect there is some truth in this. Warnock is explicit in her view on the matter.

I think that there is no doubt that women, because of their usually divided lives – trying to keep everything going at the same time – tend to excel at the subjects that take less time and probably less concentration. I know I am talking autobiographically now. You can get away with much more if you take what I think of as the ‘soft subjects’ in philosophy and therefore don’t have to take the hours in the library, or even the hours sitting when you are not to be disturbed as you work out a logical or mathematical puzzle.

Here is where I think the snooker analogy fails. Papineau claims that although there are reasons for affirmative action to increase the numbers of women (and other under-represented groups) in political institutions and technical disciplines such as law and medicine, this line of thought has no obvious application to philosophy, or to snooker for that matter. On the face of things, neither profession has the function of representing particular groups.

This hugely underestimates the importance of philosophy. I have no great concerns about the lack of female snooker players. If women are self-selecting out of snooker, I don’t feel that we have a duty towards future generations to rectify this situation. But we do have a duty to make sure women are represented in philosophy because philosophy is hugely important, in all of its forms. Even the most abstract of philosophical reasoning is not irrelevant, it is an exercise in training the mind, and the discipline and rigour needed will make one a better teacher, lawyer, doctor, journalist … generally a better human being. There isn’t much point in skipping over a length of rope for hours on end unless we take it in the context of making one a better boxer. So we need to tell all our young minds, male or female, that spending hours on a logic puzzle is a good use of their time, as it is sharpening the mind ready for other things. Philosophy matters. The technical elements feed into the practical elements. My spending hours on metaphysics was the equivalent of mental press-ups. Maybe I would go on to do more metaphysics, maybe I would study ethics, maybe I would go and be a doctor, maybe I would do none of those things. But my brain would be better for it.

Women aren’t naturally less competitive, less rational or less intelligent. If we claim they don’t see the value in abstract reasoning we are making claims about ‘them’ as a group which I would strongly argue are not innate. The value should be apparent to all young people, if the older generation is doing things right. So it is far more likely that we are, consciously or unconsciously, treating women differently, socializing them in a way that makes them feel less drawn towards academic philosophy at the higher levels. As students progress past undergraduate level the focus and dedication needed obviously increases. This could well be the implicit bias that women should be doing something more worthwhile with their time leading to stereotype threat, rather than women being innately different and hence a priori less likely to do anything ‘so silly’ as academic philosophy when they could be dealing with real things and real people. This doesn’t have to be malicious, but it could be that they are given less time, space or even patience when they are not conforming to the universal perceptions.

Of course, women are not the only under-represented group, with ethnic under-representation being a major issue. It is not the focus of this discussion, but it is worth noting that for ethnic minority females the problem is acute. In the Guardian feature ‘Philosophy is for posh, white boys with trust funds – why are there so few women?’ (January 2015), several philosophers (including Helen Beebee) give their insights into the under-representation of women. Dr Patrice Haynes, Senior Reader at Liverpool Hope University, states:

To my knowledge there are just five black philosophers working in the UK, three of whom are women – and I’m one of them.

Interestingly, she also mentions her father’s horror at her choice to study a Masters in Philosophy, and how her parents valued education that led to a secure, professional job at the end of it.

Give them time …

I have already explained why I believe philosophy to be such a valuable subject for all people and in our current political climate. This is a world where the art of rhetoric can win Donald Trump the US presidency. Leaving aside misogyny and racism, many people were shaken to the core by how someone could display such damn awful and inconsistent reasoning and be believed. Philosophy matters, and we should encourage it on every level and in every demographic. But my argument is not concerned with the number of academic professional philosophers per se. It is about the fact that in such a relevant subject there should be proportionate representation of females at every level.

I have no solutions, but there are a few steps we can take to make sure more of those bright young female minds we see at A-level and undergraduate philosophy make it further into academia. The issues are twofold. There is a perception of philosophy as irrelevant, and a tendency to be less indulgent of females in pursuing such subjects past undergraduate level, where the further up the academic ladder one climbs the more the factors I have identified will be in effect. If the former issue is rectified, then the gender imbalance should naturally rectify itself, but this would happen without the issue of how we perceive female academics being rectified and this would be only half a solution.

I don’t think we need to change any philosophy specifications or course contents to ‘fit’ the female psyche. This is because I don’t think there is one. I think that we need to leave every technical, abstract element exactly where it is. Firstly, we need to show that these are worthwhile exercises that train the mind and discipline it for other areas. I say this because this is their genuine value, not because I think women will only be interested if there is a practical application.

Secondly, we need to ensure that women are given the time, space and respect to pursue these problems. It is interesting that one of the BPA/SWIP recommendations to universities was to make sure that women in your department aren’t carrying a disproportionate share of the pastoral care in your department … reinforcing the idea that women are not being given time. Women need to know that they can get lost in logic for as long as they need.

So next time a young lady is in her room studying philosophy for hours on end, let her know she can and she should. Leave her alone, she’s in training and she’s spending her time well.

-

Author

Sally Latham is Lecturer in Philosophy at Birmingham

Metropolitan College. -

First published

Think, Volume 17, Issue 48, Spring 2018, pp. 131 - 143

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1477175617000392